While walking inside the St. Joseph Cathedral in Noumea, some may have noticed the representation of Saint Patrick on one of the stained glass windows on the wall of the eastern facade. Why does the image of the patron saint of Ireland appear here, so far from the Emerald Isle?

To have some answers, we have to go back to the second half of the 19th century. Before this period, the only Europeans to frequent the shores of New Caledonia were adventurers, traffickers and missionaries, mainly English or Scottish. But History will also remember the name of a certain Peter Dillon, a Franco-Irish navigator and explorer, who discovered the place where the Lapérouse expedition ran aground.

From 1853, the French authorities decided to settle in New Caledonia and to dedicate the territory to transportation, mainly from France. The salubrity of the climate and the presumed fertility of the soil lead them to also consider an embryo of free agricultural colonization.

However, the means of communication with Europe were non-existent. Only a few State ships have been operating from France via Cape Horn and Tahiti, capital of the French Establishments in Oceania (EFO) on which New Caledonia then depended.

Before the arrival of the French administration, some commercial links had developed with Australia and from 1854, maritime relations were more frequent. Gradually, the Australian press became more verbose about the territory, observing with interest everything that may happened on the newly colonized archipelagos located a stone’s throw from their east coast…

Advertisements touting the benefits of moving to New Caledonia began to appear throughout the press of the island-continent. For several decades, some large areas had already been hosting migrants, mainly coming from the United Kingdom.

From 1856, the first Australian investors officially declared themselves and signed the first concession contracts with the French administrative authorities. They were named Didier Numa-Joubert and Timothée Cheval, French traders already well settled in Australia. But the most famous surely was the English trader James Paddon, who has been living for several years in the islands. He also had several counters all over the Mainland and the New Hebrides.

Afterwards, those three businessmen recruited families in Sydney likely to come and exploit the land allocated to them. Most of them were German and British citizens. But a few of them were native from Ireland. They were called Newland, Ambrose, James, O’Donoghue, Daly, Casey, among others.

It had been a long time since the Irish used to be leaving their country searching for better life. As early as the 16th century, religious persecutions had pushed many Catholic families to flee Anglican repression.

Then, in the first half of the 19th century, all of Ireland was an integral part of the United Kingdom. Thereby, more than half a million Irish people left to work in English factories which have been developed within large mining areas.

From 1846, the great famine, which mainly affected the west of Ireland, caused the death of a million people and forced another two million to leave the country, mainly for other Commonwealth countries, connected to the British crown.

This emigration had always been encouraged by the British government, which saw in it the opportunity to populate the colonies. So the great migration began first in the direction of the United States and Canada. It was greatly helped by the development of the steam navy which had reduced the transatlantic crossing to three weeks, instead of twelve by sailboat.

At the same time, the reduction of the distances makes it possible to bring closer new territories that were still further away from Europe, particularly in the South Pacific.

Thus, Australia, initially a penal colony, soon attracted settlers, especially thanks to its gold mines from 1851, and to a lesser extent, New Zealand. Among those expatriates, some continued the journey to New Caledonia, perhaps inspired by the fact that the Catholic religion was naturally well established there due to the French presence.

The stained glass window on the eastern facade of St. Joseph’s Cathedral of Noumea, offered by the Irish community at the time of its construction and which represents St. Patrick appears as a testimony of this devotion.

Most of the Irish community that settled in New Caledonia therefore came from Australia, and especially from Sydney or Melbourne areas. Those two cities were already the most important in Australia at the time and the Irish community was already well-established there.

Several of these pioneer families have descendants still present in New Caledonia, as can be seen by browsing the local telephone directory. Most of them continue to have connections on both shores.

The study of New Caledonia’s civil status registers has made it possible to construct a fairly precise typology of Irish immigrants, at least those who died there or who settled there. To this should also be added all those who have just passed through, or second or third generation descendants who declare themselves as Australians, New Zealanders or Americans.

Alongside these families of agricultural settlers, there were those who came and tried their luck in others areas. Thus, a Hennessy family landed around 1858, the father, John, working as a carpenter in Lifou or Canala, before coming back to Noumea.

Another example, in 1868, a lady Casey would have held “The restaurant of wet feet” at the edge of the bay of the Moselle.

As a matter of fact, we can also observe the presence of several single women among this list. Some have come to assist the Catholic missionaries in their priesthood by becoming nuns. Others settled in town and ran small businesses in the hope of being able to marry. The ones who managed to do so, thus got the opportunity, in addition to being able to create a family, to sometimes return to Europe in more proper conditions than when they left.

On the other hand, and curiously, few single men appears on the list…

In addition to our civil status records (freely downloadable on our genealogical main pages), we can also cite the work carried out more than a quarter of a century ago by the “Cercle Généalogique de Nouvelle-Calédonie (CGNC)” on the subject and widely published in their quarterly newsletter. In addition to complete genealogies published by the families’ descendants, one can find in there many family stories and anecdotes.

The bulletins of the “Société d’Etudes Historiques de Nouvelle-Calédonie (SEHNC)” are also an important source of informations.

Finally, the descendants of several of these families have published their genealogy, which can be consulted on “Geneanet” or “Ancestry” websites. Some of these families have even been the subject of small TV documentaries on a local television channel.

Although small, the Irish community in New Caledonia has clearly inspired, by its destiny, writers of popular literature.

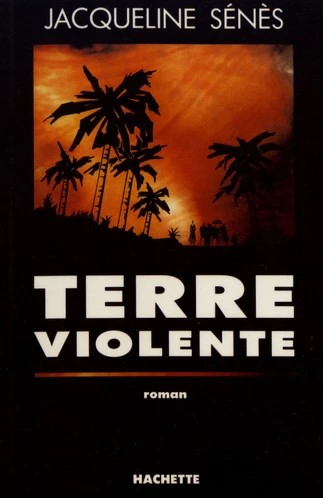

Thus, in “Terre violente“, Jacqueline Sénès stages the life of Helena, “born at the bottom of the Tiendanite valley where her grandfather O’Connell had driven his tilburys and his carts full of furniture and crockery of Dublin“. Note that this novel has been the subject of a Franco-Australian television adaptation.

In “Le Grand Sud“, the family of a certain Feargus O’Flaherty, a farmer-breeder living in the region of Saint Vincent, appears throughout the novel to help the protagonists.

Unlike the Irish of Australia or New Zealand who form a large community in their respective countries, the Irish of New Caledonia, few in number and scattered across the territory, have completely blended into the Caledonian ethnic mosaic. Along the way, they have also lost almost all cultural reference to the land of their ancestor.

However, a small association has recently been formed in order to meet and update certain traditions transmitted by their ancestors. Evidenced by this “Pudding’nade” (Irish version of cousinhood) organized last year in Dumbea, or a mass in honor of Saint Patrick, this year at Noumea Cathedral.